By Herb Gamberg

MRzine

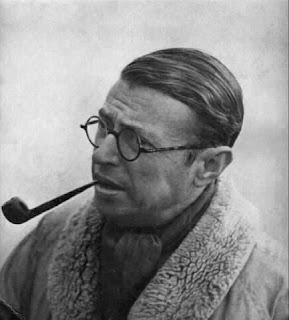

Jean Paul Sartre in the fifties made the somber remark that things were so bad at the Sorbonne in the 1920s that the University did not even have a Chair in Marxism. In asserting the fact at that time, he was of course assuming that things at mid-century had changed dramatically and that Marxism had become a vital intellectual force in French universities. Sartre in Europe could not perhaps imagine how curious his remarks sound in American context. If one reads Thorstein Veblen's account of United States universities early in the 20th century (

The Higher Learning in America) or Upton Sinclair's

Goosestep about them in the 1920s, then Sartre's headshaking about French universities appears in a different light. For Veblen and Sinclair suggest not only the absence of Marxism but the absence of any critical thought as well. Sinclair soundly demonstrates that American universities were run directly by a "plutocracy" which hired, fired, and terrorized all faculty who showed even the slightest deviation from establishment thought. The idea that Marxism might be taught in these institutions would be tragically laughable.

Except for an upsurge of Marxist thought and action during the Depression (and this upsurge was pronounced, as would be expected, almost exclusively outside universities), this abysmal state of affairs endured well into the sixties in the United States and Canada. The lowest ebb perhaps is indicated in the fifties by Paul Baran's remark that all the Marxist economists in the United States could be put into a taxicab. When I was a graduate student in sociology in the fifties, Marx was not read and, if mentioned in class, was alluded to as an interesting, but better forgotten, wrong-headed thinker. His work was at best one of the outmoded "classics." Even C. Wright Mills, who was radical but non-Marxist, was rejected as unprofessional and unscientific, seldom assigned in class, and only read in private by some students.

Read more HERE.

.jpg)