People's World

December 1 2010

Conversations with Myself

By Nelson Mandela, Foreword by Barack ObamaFarrar, Straus and Giroux, 480 pp, 2010

Watching "Invictus," the 2009 movie based on Nelson Mandela's attempts to unify South Africa through rugby, then considered an Afrikaner sport, the viewer can't help but question whether the film does a disservice by glorifying Mandela into a saint-like figure. While no one can deny that Mandela is one of the greatest heroes of the 20th century, the film seems to portray a Mandela too perfect. The character played by Morgan Freeman simply didn't seem like a person who could exist.

Given Mandela's stature, the question of whether the film went overboard is far too impolite to actually ask. Lucky, then, was the release of "Conversations with Myself," a compilation of Mandela's writings and written materials, which definitively answers in the affirmative: Mandela is as heroic as can be imagined.

Madiba, as he is often called, is primarily known for his work in leading (or, as he would emphasize, helping to lead) the struggle against South Africa's notorious apartheid system. There were many liberation fighters in the past 100 years, from Africa alone, and few if any can be remembered in the same light as Mandela. While your reviewer is not inclined to hero worship or the "great man" theory of history, it is obvious that Mandela's personal traits influenced the course of South African history and, perhaps, helped to keep that nation's transition from going awry.

The volume is ostensibly "by" Nelson Mandela, but, as the editors admit, it was pieced together by committee. It is a collection of his writings and conversations, of diaries he kept and even notes he jotted down on a calendar. While this makes for choppy and sometimes frustrating reading, it provides the clearest glimpse yet into the mind of a man who is by nature private and reserved.

|

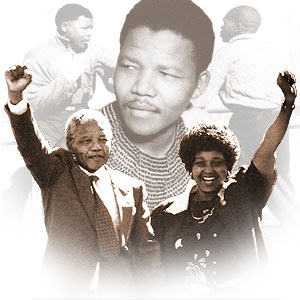

| Mandela in the 60s |

The MK was a military organization, and it fought, engaged in violence and acts of terror (never aimed at civilians). But Mandela argued its necessity on two fronts: first, it was morally necessary to fight physically for a democratic society, as violence from the MK was nothing compared to violence from the apartheid state, and the MK's goal, a free society, would end all forms of terror.

Secondly, relations between the black majority and the white minority government had become so bad that violence was bound to break out. Without the formation of the MK, which would organize violence, Mandela argued, acts of terror that could push the country to the brink of chaos would erupt.

The seeming contradiction between Mandela's love for peace and his willingness to fight is no contradiction at all: Mandela simply did what was necessary for justice. And he, even in the face of criticism from his comrades, refused to give up on the notion that all people share a common humanity, that all people can be good.

Perhaps the most shocking sections of the book are the passages in which Mandela considers his white oppressors. While sitting in a prison, in the midst of brutality, even after white officials refused his pleas to attend the funeral of his mother and of his son, the future leader wrote about the need to show "respect" to the guards. Of course, he wasn't writing out of deference to white authority: he simply saw even his warders as human beings working positions into which they were born.

In a particular diary entry, Mandela reflects upon his treatment of a young Afrikaner guard who was rude to Mandela. Madiba insulted the guard in front of the other prisoners, and was, apparently, punished. But instead of writing with bitterness, the liberation leader considers that the guard was rude because he was young, new and looking for respect from his peers. Mandela went to apologize: no revolutionary phrase mongering, nothing overtly moralistic - just simple human compassion.

Of course, it was always the position of the ANC that a nonracial society was for the best, and that everyone should be treated equally, regardless of their skin color. Still, seeing an example of that position so sharply personified is jarring.

When apartheid was overthrown, and the black majority finally won the right to vote, electing the ANC to lead the country, the transition was overwhelmingly peaceful. Despite provocations from the police, and despite years of suffering at the hands of a cruel white ruling caste, retribution never came to the white minority. How any people were able to act with such class and dignity after all that happened was always beyond this reviewer, but as his personal notes make clear, President Mandela played a major hand in that, and in influencing South Africa to become a nonracial nation.

As choppy as the book had to be, the insights derived from it lend a great historical worth. Be warned, though: a portion of the book, several dozen pages, is tedium encapsulated. Page after page of entries Mandela made on his calendar are reproduced, though, for the sake of brevity, much was left out. Reading through these pages becomes something of a chore, and the urge to skip forward is hard to resist. Whether or not the editors intended this, a point has been made: the reader can't help but think to himself how wretchedly awful life must have been inside prison for Mandela to have meticulously recorded even how many ounces of Vaseline hair oil he was given.

Towards the end of the book, Mandela argues that he's no saint, not even by the definition of someone who "sins, but keeps on trying." Your reviewer finally found something in Mandela's writings with which he could disagree

No comments:

Post a Comment