America's battle over health care reform started in Saskatchewan

By Christopher Flavelle

Slate

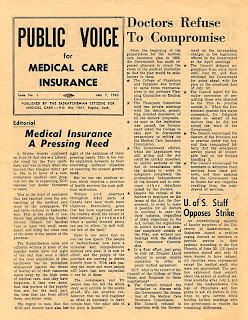

Nearly 50 years before Sarah Palin gave us "death panels," the American Medical Association was testing the limits of health care scare tactics in the Canadian prairies. During the 1960 provincial election in Saskatchewan, the AMA helped fund an advertising campaign aimed at defeating the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, a quasi-socialist party whose leader, a former Baptist minister named Tommy Douglas, had promised to introduce universal, government-funded health care in the province.

The AMA, together with Saskatchewan's College of Physicians and Surgeons, warned that if the CCF won, doctors would leave the province in droves. But here was the kicker: As Dave Margoshes writes in his 1999 biography of Douglas, the campaign told voters that if the state were permitted to take over health care, "patients with hard-to-diagnose problems would be shipped off to insane asylums by bungling bureaucrats."

The campaign failed. Douglas won the election, and the CCF government went on to introduce his health care plan in 1962, creating the model that the rest of Canada would later follow. (So far as we know, insane-asylum panels did not come to pass.) But the fight for health care reform in Saskatchewan, which the AMA worried could spark change in the United States, was a precursor to the battle in America today—a mix of populist anger, political opportunism, and disinformation. As Democrats debate whether to pursue health care reform in the face of growing opposition, they might consider the lessons of Saskatchewan.

Like the Democrats after their 2008 victory, the CCF moved slowly at first to implement its plan, a delay that emboldened the opposition. In an attempt to win the support of doctors, the government created an advisory panel for their concerns. Doctors used the panel to stall, and the government waited more than a year to pass its reforms, with the start date delayed until July 1, 1962. The province's doctors responded with a vote to strike if the plan was implemented.

The events of the next 10 months were ugly by Canadian standards. Douglas' push for health care reform "lit the fuse of the incendiary bomb that would tear Saskatchewan apart into its two opposing elements," wrote Doris French Shackleton in her 1975 biography of Douglas.

Part of the unrest came from doctors themselves. In the months leading up to the new plan, physicians across Saskatchewan put up office signs reading, "Unless agreement is reached between the present government and the medical profession, this office will close as of July 1." Douglas' wife, Irma, described how a doctor would tell his pregnant patient, after a check-up, "I'm afraid this is the last time I'll be able to see you."

The doctors' worries about being paid by the province, rather than patients, may have been genuine. But those concerns were amplified by Saskatchewan's opposition Liberal Party, which had been shut out of power since 1944. Like the American Republicans 50 years later, the Liberals fought health reform in two ways: directly, by opposing it in public; and indirectly, by supporting groups that could provide the appearance of broad-based public anger. In Saskatchewan, the public opposition to health reform came in the form of a movement called Keep Our Doctors, which organized rallies and protests across the province.

Sometimes, the Liberals blurred the line between political opposition and rabble-rousing. At a Keep Our Doctors rally outside the provincial legislature, Liberal leader Ross Thatcher used the occasion to call for a special session of the legislature, which wasn't sitting at the time. To illustrate his point, he invited TV cameras to follow him up to the locked doors of the legislature, which he then made a show of trying to kick down.

But in another precursor to today's Tea Party movement in the United States, the unrest over health reform in Saskatchewan proved to be more than just political theatrics. "The fears inspired by the doctors and fanned by the Liberal party," Shackleton writes, "convinced many people at least briefly that the CCF was a dictatorial, power-mad, ruthless group of politicians who would rather see people die for lack of medical care than back down." Shackleton described "a sense of civil war." (Read more about the unrest in Saskatchewan.)

Public anger against the plan found its lightning rod in Douglas, who had resigned as Saskatchewan's premier to run for federal office as the member of Parliament for Regina. Election Day was June 18, 1962—just two weeks before the new health care plan was to take effect. A woman who worked on Douglas' election campaign recalled the venom of the time. At night at the campaign office, "teenagers would come up and hiss at us through the glass," she remembered later.

"The city's residents had been whipped into a near-hysteria by the doctors' anti-medicare campaign," Margoshes writes, adding, "There were graffiti threats on city walls and calls in the middle of the night to Tommy's house. His campaign manager, Ed Whelan, got frequent calls from a man threatening to 'shoot you, you Red bastard!' A few homeowners placed symbolic coffins on their front lawns."

As in the United States today, opponents of the health reform plan weren't sure whether to denounce the CCF as Communists or Nazis, so they did both. Protesters greeted Douglas' motorcade with Nazi salutes—when they weren't throwing stones at it. Other opponents painted the hammer and sickle on the homes of people thought to be associated with the party.

The doctors made good on their threats: When the new health care plan was introduced on July 1, doctors across the province walked off the job. But the government was ready, flying in replacement doctors, mostly from Britain. The strike ended after three weeks, the health care plan stayed in place, and four years later, the Canadian government passed the Medical Care Act, which provided funding for every province to create a similar plan.

Douglas and his party were vindicated. Once their plan took effect, Shackleton writes, it "was soon so well accepted that no political party had the temerity to suggest its abolition."

But that vindication came too late. Douglas, who had led the CCF to five straight provincial victories, lost his federal campaign that June, receiving barely half as many votes as his opponent. Two years later, the Liberals defeated the CCF for the first time in 20 years. The party that passed health care reform would spend the next seven years out of power.

The events leading up to the 1962 doctors' strike in Saskatchewan are different from today's Tea Party movement in important ways, of course. Saskatchewan wasn't seized by the same level of broad distrust for government that U.S. opinion polls show today. The idea of a government role in health care was already accepted, to a degree: Saskatchewan had already passed the Hospital Insurance Act in 1947, which paid for hospital care. And the changes Democrats have called for stop well short of single-payer health care, notwithstanding the charges of their critics. Even the AMA supported Obama's plan.

But the anger of those months in Saskatchewan undermines a key belief in the debate over health care reform. When confronted with the overall success of Canada's brand of government-funded health care—better health outcomes at much lower cost—Americans tend to respond that such a broad government role is anathema to American culture. This has the ring of an excuse—after all, the idea was apparently somewhat anathema to Canadian culture in 1962. As Douglas said then, "We've become convinced that these things, which were once thought to be radical, aren't radical at all; they're just plain common sense applied to the economic and social problems of our times."

The point isn't that U.S. and Canadian cultures aren't different. Rather, it's that cultural attitudes aren't static. However much some segments of U.S. culture may resist Obama's proposals, the Saskatchewan experience suggests that resistance will dissipate if the plan produces a system that works better than the status quo—especially since, as in Saskatchewan, the government was elected on a promise to make that change.

The other lesson of Saskatchewan is less exciting for Democrats: Even if people come around to the reform itself, they may not come around to the party that pushed it through. If they want to achieve health care reform, that may be a chance that Democrats have to take. But re-election qualms shouldn't be dressed up with bromides about the limits of what's possible. As Canadians can attest, health care reform takes a little more backbone than that.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Doris French Shackleton, a biographer of Tommy Douglas, describes the mood at the time:

The anger crackled in the air. Every business interest, every insurance agent, every local Chamber of Commerce … now aided and abetted the doctors' cause with every resource at their disposal. Stores were closed to swell "Keep Our Doctors" rallies and parades and marches on the legislature. Newspapers and radios bristled with accusations. There was, as many testified, a sense of civil war.

Shackleton tells of the story of an elderly priest, Father Athol Murray, inciting a "Keep Our Doctors" rally in Wilcox, a small town 25 miles south of the provincial capital, Regina. "This thing may break out into violence and bloodshed any day now," Father Murray told the crowd—"and God help us if it doesn't."

A volunteer on Tommy Douglas' federal election campaign, which came at the height of the unrest in Saskatchewan, tells this story: "I drove home one day with a taxi-driver. He was a man who could really have benefited from Medicare. He had no teeth: he had had them all extracted. He said he had five children and a sick wife. And he blasted me about Medicare and about Tommy. There was no arguing with him."

Christopher Flavelle reports for ProPublica, the nonprofit investigative newsroom in New York City. He is Canadian.

Article URL: http://www.slate.com/id/2245037/

Become a fan of Slate on Facebook. Follow us on Twitter.

No comments:

Post a Comment